Honest Communication Kills Weaponized Incompetence

It’s only human to need help — but we have to be able to admit it.

Welcome back to Autistic Advice, a semi-regular advice column where I respond to reader questions about neurodiversity, accessibility, disability justice, and self-advocacy from my perspective as an Autistic psychologist.

You can submit questions or suggest future entries in the series via my Tumblr ask box, or you can email questions to askdevonprice at gmail.

Today’s question is actually multiple questions — all wondering about how to reconcile the challenging realities of disability with the potential for damaging, sexist weaponized incompetence in housing situations:

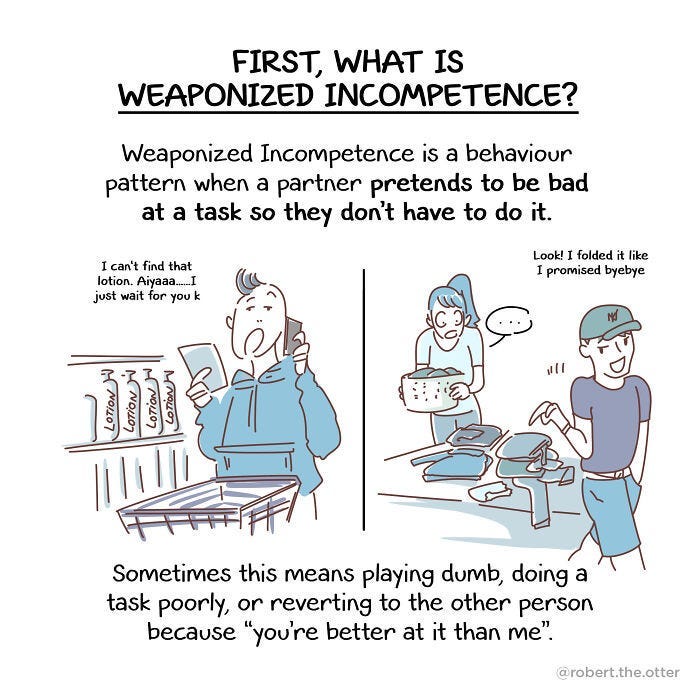

For the uninitiated, let’s first address these questions by acknowledging what weaponized incompetence is. Broadly speaking, to weaponize incompetence is to pretend to be far worse at a task than you are genuinely capable of being, in order to ensure you are never asked to complete the task again. If you’ve ever spitefully filled the dishwasher in the most haphazard, messy way possible in order to get a nitpicking roommate to expect less of you, or simply to express your frustration at their perfectionism, you’ve had a taste of what engaging in weaponized incompetence feels like, and its possible use cases.

The concept of weaponized incompetence was originally introduced by business writer Jared Sandberg, in a 2007 article for the Wall Street Journal in which he described an HR executive shrugging off the responsibility of planning the company picnic by asking so many infuriating questions about what a picnic even was and how a person would go about planning one that eventually somebody else took on the load of planning the event.

“The inability to grasp selective things can be very helpful in keeping your desk clear of unwanted clutter,” the HR executive explained of his strategy.

Interestingly, in his original piece Sandberg describes feigning incompetence as a useful tactic for reducing one’s workload in a professional setting — and in the workplace, asking questions, dragging your feet, and half-assing things are real skills that are useful for covertly setting boundaries and not taking on what is not your responsibility!

Eventually though, the term weaponized incompetence would take on an exclusively negative connotation and start getting applied mostly to domestic chores.

Personally, as a proponent of ‘laziness’ and an outspoken hater of labor exploitation, I’m all in favor of people slowing down their work flows, letting errors that are not their problem slide, and asking a tedious number of questions as a way of reducing the heat their managers place on them. Generally speaking, I would recommend that workers learn the fine art of only doing what they are literally told to do and nothing else (also known as malicious compliance) and not picking up the higher-order responsibilities of monitoring work process or anticipating problems when they are not compensated for it. Making the world frictionless for others offloads an immense amount of stress and unacknowledged responsibility onto you.

Frictionless for Whom?

Seamlessness isn't always neutral. It's often subsidized-by someone else's time, attention, and emotional capacity.substack.com

Unfortunately, today ‘weaponized incompetence’ doesn’t mean having shrewd professional boundaries and knowing when to let a manager’s request for a volunteer to hang in the air. Now it means exploiting the people you’re close to in your private life by deliberately sabotaging shared household responsibilities. Take for example this comic illustrated by Robert the Otter, in which a careless husband disappoints his spouse by purchasing the wrong groceries and leaving the laundry in a sloppy pile:

Since disabled people are quite regularly haunted by accusations of faking our conditions, or failing to try sufficiently ‘hard’ at meeting expectations, it is no wonder that accusations of weaponized incompetence particularly sting us.

When I was writing my first book on laziness, I heard from dozens of ADHDers who had been relentlessly branded as lacking motivation and organizational skills for all their lives, beginning with their parents and teachers. Virtually everyone in their lives mistook their need for social support as they were completing tasks for proof they didn’t really care about getting anything done.

The ADHDer couldn’t run their lives like little business executives (incidental, neither can real CEOs): like most human beings, they needed a structure, a timeline, and some help, otherwise they tumbled into depressed and under-stimulated despair. But since laying on the couch staring at the wall frozen doesn’t look like being in distress to most people, they were assumed to just not be trying enough.

It’s not just neurodivergent and mentally ill people who get accused of weaponizing incompetence: physically disabled people are accused of being lazy fakers in the same way too. Take for instance the sheer number of mobility aid users who get accused of fabricating their conditions for handicap parking tags. If a person uses a wheelchair or a cane but is capable of walking for a short distance, the odds a stranger will confront them for “faking” or report them to the authorities is absolutely sky-high.

Within my own life, unfair accusations that I’m weaponizing incompetence have largely been centered on my lack of physical abilities. My Autism physically incapacitates me in ways others can’t see. It takes me a very long time to learn any new physical skill, my muscle tone is quite underdeveloped, and I’m quite uncoordinated, with a slow reaction time and a hair-trigger flinch response. I’m also hypermobile as shit, with floppy weak hands.

As a child, the adults around me really couldn’t wrap their minds around my seeming physical ineptitude, even though it was bad enough to see me placed in special education classes. To everyone I looked like a non-disabled child, though they frankly wouldn’t have shown much sympathy if I had been visibly disabled either. Gym teachers and classmates got frustrated with me when I had to manually teach myself to skip in an arduous step-by-step fashion: Foot on the floor. Now hop. Put the other foot down. Lift the original foot up. Hop again. For abled people, such activities were seamless and intuitive. If I couldn’t do it just as easily, it was clearly because I wasn’t trying hard enough and wanted to waste everybody’s time.

My fine motor skills were also quite poor, so I was kept inside during recess to practice my cursive. My teachers believed I was just being careless by writing in such a shaky, hard-to-read script, but I couldn’t make my fingers obey no matter how hard I tried. (Eventually, I would find social tolerance for my bad handwriting by becoming both a man and a doctor).

It frustrated me to no end that my most desperate attempts at good performance not only weren’t good enough, but were assumed to be my worst possible attempts. The suspicion that was generated by my best efforts made me want to disengage, to not try at all. I was afraid to participate in any kind of physical activity or hobby requiring dexterity for a great many years afterward, fearing that my shitty, disabled performance would be viewed as weaponized incompetence.

Even some otherwise trusted relatives and friends made snide comments about how messily my desk was organized or clumsily I performed life tasks like cleaning or cooking. I forgive them, they simply had no idea I was disabled at the time. But that shit stung.

I share all of this to acknowledge that the two question-writers’ grievances with the idea of “weaponized incompetence” are quite reasonable. Far too often, disabled people’s most extreme, unsustainably intense efforts are still viewed as maliciously insufficient.

But at the same time, weaponized incompetence is a very real dynamic of manipulation, typically one that is highly gendered and racialized — and because it tends to thrive off of systemic oppression, it’s also one that tends to offload responsibility onto disabled people more often than not.

Ask any woman who dates men about her experience with weaponized incompetence, and you’re likely to hear a litany of horrific examples.

A co-parent pretends to take an hour-long bathroom break after every single dinner so that he won’t be expected to wash the dishes. A boyfriend fills the washing machine with dish soap and ruins all the clothes. A spiteful male co-worker creates the most hideous PowerPoint decks imaginable, and says his female colleague has a much better eye for such things than him. This Reddit thread is filled with real-life instances of weaponized incompetence, if you’re in need of a little rage porn today.

Weaponized incompetence is also leveraged by other majority-group members, in order to take advantage of the efforts of marginalized people. White people often cope with our self-involved racial anxieties by pretending to have no knowledge about racial justice issues and no viewpoints of our own, forcing the Black and brown people around us to explain everything with unfailing patience and create ideas as to what we should do.

(Usually, us white people complain that what they are ‘demanding’ of us is too much and that they asked for it in the wrong tone anyway).

When trans women explain their experiences of transmisogyny, non-trans-women often respond by pretending the concept is too ‘confusing’ or ‘academic’ for them to ever understand. In doing so, we TME people absolve ourselves of any responsibility to do anything about it.

Managers quite frequently feign incompetence when it comes to matters of workplace injustice, and then volunteer their most marginalized employees for committees and initiatives to address such issues so they don’t have to.

These are systemic patterns, but they also emerge in our private lives. A darker-skinned Black man that I know was once in a long-term relationship with a far lighter-skinned Black woman who was emotionally abusive toward him. After he escaped her, she revealed to him that the numerous times she had ‘lost’ her driver’s license and car keys had been completely on purpose, so she wouldn’t have to find a job and could keep relying on him financially.

Similarly, an abusive ex-boyfriend of mine once confessed that he deliberately ‘forgot’ his wallet at home when we went on dates, because he wanted me to pay for our meals. He reasoned that though we were making the exact same stipends in graduate school, I deserved to pay more than him because I had a savings account. (Of course, the only reason that I had a savings was because I was more responsible with money than him. He had wealthy relatives helping to pay his way through school and I didn’t, so I’d had to develop a competence in budgeting he never did).

It bears mentioning here that a person doesn’t need to be consciously or intentionally weaponizing incompetence in order to benefit from it. In many of the examples I’ve outlined above, it was a planned tactic, but in many cases it’s simply reinforced by existing social structures and expectations in a subtle way. White women and white men have a lot to gain from others seeing them as powerless and taking care of them and their emotions. If a grown man has always had a girlfriend around to scrub the shower, it might not even occur to him that he’s lacking in a skill.

Another ex-partner of mine absolutely benefitted from weaponized incompetence; I did almost everything financially and logistically for the entirety of our relationship. He was also almost certainly an undiagnosed ADHDer who was struggling immensely with shame about his own disorganization and lack of motivation and was profoundly depressed.

From my perspective, it didn’t matter. I still ended up having to sign up for all the utilities, pay all of the bills, figure out a new place to live three different times when our rent went up, hire the movers, remind him to get a new ID when his old one was expired and we had a flight coming up, find him a dentist when his tooth was aching, help him write work emails, ask him to clean things rather than being able to trust he would contribute, repair everything that broke, make all the decisions regarding decluttering the house, take care of our pet, and on and on and on.

My ADHDer partner deserved more help than he ever got, as a (very likely) disabled person living under capitalism. Before me, he’d been sleeping in an unheated room with no hot water and moldy dishes spilling out of his sink. He got sick constantly and had to sell his blood plasma in order to buy fast food to sustain himself on. After we got together and I started taking on some of the mental and emotional load that he couldn’t muster, his life stabilized and improved.

But I also shouldered his life burdens in a way that made me miserable as a fellow disabled person. It drove me nuts and made me dysphoric to admit it, but a large part of how we wound up within that dynamic was systemic sexism, because he was a cishet man and I wasn’t. When we got together, I was a ‘woman’, and some of the routines established early on in our relationship were rooted in traditional gender roles, and never got reset.

All that said, and my considerable real-life biases having been put on the table, I do think it’s the case that many disabled people are unfairly accused of ‘weaponizing incompetence’ when all that they’ve done is express a limitation as clearly as they possibly could, which ought to be a good thing! There is nothing wrong or manipulative with asking for help, or for articulating what you are and are not capable of, as honestly as you can.

This honest communication piece, by the way, was absent in the relationship I just described. My ex-partner wouldn’t even acknowledge that he wasn’t contributing and could not contribute to our life together in any practical way. When I tried to name that dynamic, and express my frustration, he would shut down, walk away, say things were going to change without any plan for how that might happen, or tell me that he was facing so much stress in his life at the moment that he wasn’t available to have a discussion (and of course, his life never stopped being so crisis-level stressful that he couldn’t talk, even after multiple years).

The reality is that the lines between all these things can be blurred, as a person’s intent and their impact can be wildly different, and there is rarely enough support to actually go around. People who are doing their best can still leverage sexism and leave a partner feeling taken advantage of. And a partner who feels taken advantage of can have real reasons for feeling that way and can also still be ableist or cruel to their disabled loved one.

In my frustration with my ADHDer partner, I was sometimes downright mean! Eventually I just stopped asking him to do anything around the house and would just angrily do chores at him. I made numerous important household decisions without ever consulting him. My anger absolutely contributed to his emotional shutdowns and shame-spirals. I was not able to ask for the support that I needed, or to get him to talk about why he was feeling so stuck, and so I stopped seeing the relationship as a partnership and began to treat him as a weight.

All of these difficult issues only metastasize when covered by layers of avoidance and shame.

If you’re disabled and worried about unfairly weaponizing incompetence, know this: The difference between weaponized incompetence and responsible behavior is honest communication.

A guy pulling a weaponized incompetence maneuver on his girlfriend is not being honest about what he is capable of, and he’s intentionally not communicating about chores or life responsibilities whatsoever, hoping that his partner will see him fake-fumbling and pick up the slack.

But if you can honestly and directly tell your housemate or spouse what you are and are not capable of, they have the power to decide if they can handle it — and if you can work with them to strategize potential solutions, you are not engaging in weaponized incompetence. You’re collaborating to find a solution to a shared problem. The other party also has the right to decide they can’t take on that load (they may have their own disabilities and limitations too, after all). But they also need to be honest about that, too, rather than being insincere and resentful.

If both parties can be realistic and remain present for a real conversation about shared responsibilities and limits, then nobody involved is doing anything wrong — even if you ultimately arrive at an impasse and have to live separately or break up!

One Autistic woman that I interviewed for Unmasking Autism, Reese Piper, shared with me that she tells prospective roommates that she is incapable of keeping up with the dishes. This allows her potential housemates to make an informed choice about how they want to live. When last I saw her, Reese had a healthy, mutually supportive relationship with a roommate she had been living with for multiple years. Reese wasn’t weaponizing incompetence to make someone else do all the dishes. She was honestly communicating about where she needed help.

Every disabled person has to arrive at a distribution of household duties that works for them — and they should do it clear-headedly, rather than having to lie or apologize for how they work. Unfortunately, due to the pressures of capitalism and hyper-individualistic contemporary life, some people simply can’t arrive at an arrangement of household duties that fully functions. The expectation that anyone be capable of working a full-time job and maintaining a clean home and keeping themselves fed is completely unrealistic — it’s not even possible for abled people, to the extent that’s an identifiable human group. It’s definitely untenable for most disabled people (and remember: all humans eventually become disabled, if they live long enough).

This introduces a whole other layer of frustration and difficulty to the topic. Those who can afford it can hire home cleaners to cover gaps, and should pay them extremely well — and we all should be moving towards a model of communally preparing food. But in practice, very few disabled households have access to such things, and end up relying upon an army of poorly-compensated GrubHub drivers, Taskrabbiters, and Amazon delivery drivers to provide them with the resources & services that a more equitable society would put actual public systems in place to provide.

As disabled people, we are unfortunately forced to plan around our own inability and lack of resources, and plan for the eventuality that we’ll need ever greater support one day than we do now. Because we’re poorer and less socially connected than abled people, building a sufficient support network is incredibly difficult. These are all valuable things for us to start discussing frankly and work to build alternatives to. Much of my new book, Unmasking for Life, concerns planning for the future in these ways as a disabled person.

Where it is not helpful to invoke the evils of capitalism, however, is when it is used to silence the frustrated girlfriend or wife of a man who is weaponizing incompetence and just wordlessly offloading the burden of all domestic life duties onto her.

Yeah, capitalism is unfair and unwinnable, but that’s not a reason for Jennifer to be any less infuriated at Bradley for leaving piles of beer cans and boxes all over the flat surfaces of the apartment, never checking the mail, and letting the dog shit on the floor. He’s making her hyper-independent life under capitalism even harder by handing her obligations that she never agreed to. It’s certainly not ableist for her to decide this is a raw deal and that she wants the hell out, whether he’s got a diagnosis that helps explain it or not.

Capitalism is, however, a useful variable and stressor to consider for two disabled people who are living together, are open with one another about what they can and can’t do, and who still run into very serious roadblocks and fights despite it. In that situation, taking a step back to name the impossibility of the present situation can help cool down fights and remind everyone involved that they are on the same side.

After all, all the honest communication in the world can’t change the fact that two people’s needs and abilities aren’t perfectly compatible, or that neither of them have enough money, time, or spoons to hold things together. Sometimes you just gotta admit a situation sucks, and decide whether to tolerate a little mold in the sink or just stop living together. Even on the idyllic trans space commune of our dreams, some people will still not make good housemates with one another.

This brings me to our next question, from an anonymous Tumblr user who wants to know who holds the responsibility for getting an inequitable living situation back into balance — who should reduce their expectations, and who should volunteer to find a hack or accommodation that helps them to do more? — and how to weigh concerns about ableism, racism, and sexism against one another so that no one gets taken advantage of:

There are a lot of valuable nuances to unpack in this question. First, I agree with you Anon that when housemates find themselves at an impasse when it comes to chores, the solution is often to revise expectations about what a functioning household “has” to look like, which chores are actually necessary, and how those chores get done.

As Marta Rose has written about frequently, disabled people will only be met with failure and frustration when we try to make an idealized abled life fit our minds and bodies. If you have a family that grazes snacks all day long because they cannot handle the sensory experience of a full belly, then why stress about maintaining a spotless dining room? Why cover the back yard in difficult & wasteful-to-maintain grass imported by Europeans if you have a special interest in native grasses and would love the sensation of a rock bed beneath your feet?

By throwing out the rules about what a responsible “adult” life must be, you can bring your environment into greater alignment with what you actually need. For example, I have two disabled friends who sleep together in the same bed in their small apartment. They can’t afford to live in a bigger space, and they do not plan on dating or living with romantic partners, so sharing a bed and bedroom simply works for them.

This doesn’t fit other people’s scripts for what a platonic relationship ought to look like, but who cares? It means fewer sheets to wash, less rent to pay, an easier time lining up their schedules with one another, and the comfort of being close to a trusted buddy at night. It’s an arrangement they both have communicated about and are compatible on, and it spares them a lot of stress.

The example of using paper plates, here, is instructive: a lot of housemates with busy schedules and competing disabilities drive one another crazy fighting over the dishes because they’ve been taught that’s a household duty that simply must get done. But instead, could you live with an overflowing sink and an automated air freshener to cover up the stink? Could you swap to disposable plates? Can you ask a friend to come by and do a big dish-cleaning session once every week in exchange for a home-cooked meal and some weed? Could you rely on takeout and convenience meals more often, or follow one-pot recipes?

Humans have depended on food carts and communal cafeterias since before Ancient Rome, after all. Why do we begrudge our disabled bodies for needing a little outside help? It is okay if none of these particular setups would work for you, but the point is to not take any standard arrangement or value system as a given. I know multiple eco-conscious people who keep reusable rags in their bathrooms instead of toilet paper. It’s not for me, but it’s admirable that it works for them! There are no rules!

Of course, if we are going to rethink our relationship to household labor, we have to be able to talk openly about what we need and what rankles us, and to hear what our housemates have to say. And this is often where the negotiation breaks down. Tumblr user Margaerstyrell shares about a time when they were unable to admit to themselves or anyone else that they couldn’t keep up with their dishes — and their roommate couldn’t be honest about how much that bothered him.

“I used to be the roommate who didn’t understand how disabled they were and had a sink full of dishes,” they say. “It got to the point where a former roommate moved out because he refused to engage in an actual conversation about it, and insisted it was fine until one day he couldn’t pretend anymore.”

At the time, Margaerys thought their arrangement was acceptable, since they were dealing with incapacitating back pain, and their roommate had never said that keeping the sink clear bothered him. “In hindsight I should’ve been more proactive about finding alternative solutions but was ashamed at the idea of paper plates and ashamed at the idea of asking for help from someone else,” they say.

This case really demonstrates how shame can block an effective negotiation on both ends of the dynamic. Disabled people often feel ashamed of all that they cannot do, and their loved ones and caregivers (a majority of whom are also disabled in some way) often are ashamed that they can’t handle the responsibility of covering it all. It can be useful for all parties to look over an Activities of Daily Living checklist, as well as a chore checklist, and really hash out what isn’t possible, where help is needed, and which responsibilities they can let slide.

Housemates can also work together to rank chores in terms of their enjoyability or importance. That way, the division of duties reflects each person’s priorities, and when a crisis inevitably happens, the pets can remain fed and the pills put into the sorter, even while the toilet turns into a science experiment.

Beyond all this, the fact remains that all the communication skills in the world are powerless against a closed ear. Some people have deep-seated domestic anxieties that are all about managing how they are seen, and find it intolerable for their hedges to get overgrown or the windows to be streaked with bird shit. Sometimes partners become so bitter about years of perceived unfairness that they don’t even want to take on the work of processing about it anymore.

In cases like these, the only solutions are to cope with the unfairness for as long as it’s necessary, and dissolve the living arrangement as soon as it’s possible. The more communicative partner should try to minimize the financial and logistical strain that this change creates, where possible, and make sure not to damage any of their housemate’s property or invoke the authority of landlords or the police in order to make their break.

Unfortunately, it is all too common for white and transmisogyny-exempt people to weaponize their status against housemates who are Black, brown or transfemme, and escalate a small conflict over laundry into accusations of abuse, arrests, and evictions. It is very common for a white or transmisogyny-exempt person to weaponize anti-Blackness or transmisogyny against a roommate who speaks up about inequity and portray them as the aggressive one.

This brings me to the Anon’s final great question, about how to navigate concerns of weaponized incompetence alongside the desire to not commit racist aggressions or take advantage of women’s labor. As he rightly notes, it is often women and people of color who get unfairly saddled with the majority of domestic duties, and it’s frankly easier for white men to set boundaries based on disability and have them taken seriously. Hell, one of the major reasons that advice columnist Captain Awkward banned talk of diagnoses from her comment section was because people were so quick to use neurodivergence as an excuse for the failures of every irresponsible dude.

I do think, however, that sometimes the fear of creating an unjust living environment prevents housemates from fully being honest with one another about what they need. Very socially conscious people can sometimes turn what must ultimately be a personal discussion of limits and needs into something that is far more symbolic.

Most people have the best of intentions when they try to be mindful of how race and gender intersect and interplay with the division of chores, but in practice a lot of times people use their political ideals as a reason to argue against their own feelings or to not be candid. One of the ways that white men offload a number of household responsibilities onto those around them is by failing to ever talk about any of it. And one of the ways that white people create environments of hostility with our roommates of color is by simmering with resentment and never voicing our concerns until we find a suitable excuse to play the victim and let it all spill out.

I think a person has to be able to tell their roommate when they are being an asshole. I think a person should just be straight up if they don’t see the point in putting the shoes on the shoe rack. It is better to have the open conflict and try to settle the issue than to pretend to be a person without friction.

Before somebody gets way too much in their own head about how a particular conflict looks or what structural issues might be relevant in the abstract, they really have to start from a baseline level of self-acceptance, and be able to articulate both what is hard for them and when they are fucking cheesed at their roommate for not doing what seems like their fair share. If you feel like you can’t name those things, you’re never going to actually have a respectful, functioning relationship.

To the anonymous question-askers who wrote in, I hope that you found this exploration of weaponized incompetence helpful. And to all the disabled readers who have harbored fears that you’re taking advantage of other people and not doing enough, I hope you can find the clarity to name exactly what your needs are, and the safety and support to voice that reality without being shamed.

To all the women, people of color, and other marginalized people who are carrying an overlarge burden, I hope you can find the freedom to drop the rope and leave all the people taking advantage of you scrambling to solve all their problems themselves.

And to everyone reading this: let’s remember that we are each capable of manipulating and of being manipulated, or being thoughtless and of being overlooked, and that we all must take care of one another. This begins with being honest about what we need for ourselves.

Oh hey that's me at the end! Happy to report I'm a much more honest and open communicator w my fellow disabled nesting partner and we navigate stuff pretty similarly to the solutions described. Paper plates, reducing expectations of what clean is, outsourcing labor when shit hits the fan and neither of us have the spoons. It is possible friends

This is a great unpacking of all these overlapping issues - thank you! One thing I would add is that the social cost of uncleanliness is often not evenly distributed (see studies like this one which found that both women and men see mess as worse when they see it as a women’s mess: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0049124119852395). The question of where to compromise on standards is really important, but I have been frustrated by having men say that the women in their lives are too fussy without any self-reflection on what might trigger that “fussiness”.